Flesh and Bone

Abhay Sardesai considers the contract between word and image in the works of eight artists.

Youdhisthir Maharjan. The Code of Love. Acrylic on reclaimed book pages. 14.25” x 9”. 2017. Image courtesy of the artist and Tarq. © Youdhisthir Maharjan, 2018.

1.

The word and the image have often behaved like the best of friends and the worst of enemies. From Dadaist photomontages to Conceptual commentaries, they have exchanged enthusiasms, cut into each other’s orbits, interrupted each other’s flows and engaged in prolonged inter-play. The frisson of excitement that this has generated has generally been good news for art.

Contemporary artists have steered these diverse signalling systems to startling effect. In the hands of an able practitioner, their shared ecologies have led to intense aesthetic experiences and multilayered signification.

2.

With a critical self-awareness, Atul Dodiya locates himself at the grand confluence of diverse expressive forms – European, Bengali and Hindi cinema; European and Indian literature; and classical and modern art. He often uses this rich and copious inheritance to fashion a formal and substantive response to insistent public and private histories through his artworks. The written word and the echoes it has gathered over time become an endless resource for his mosaic of quotations.

A similar experience of de-familiarisation awaits the viewer as she moves around cabinets packed with carefully appointed artefacts – startlingly contemporary and tellingly kitschy – at 7000 Museums: A Project for the Republic of India (2014). At the back of the showcases are paintings that carry the full text of poems from the irrepressible Arun Kolatkar’s Kala Ghoda cycle. The city of Bombay is full of surprises, Dodiya seems to suggest, and its alienations are often its intimacies.

The Bako Exists. Imagine series (2011) has ‘blackboard’ paintings on canvas with long conversational passages between Bako and Gandhiji. As they chat in their shared dream-space about eating mangoes, praying and examinations, Dodiya’s rendition of Labhshanker Thaker’s work of fiction creates a level playing field between the child and the Mahatma. The inscribed text cuts through false pieties and offers a surreal meditation on innocence and irreverence. In fact, out of his 200+ paintings featuring the Mahatma, there are quite a few that feature pages from his diary or recreate receipts and notes.

If Dodiya culls tactically and with great feeling from literary genres, it is the historical address that Jitish Kallat re-visits to measure the distance yawning between the past and the present. The installation Public Notice(2003) carries Jawaharlal Nehru’s moving ‘Tryst with Destiny’ speech written with a rubber adhesive on five acrylic mirrors that have been set ablaze. Kallat’s rage at the Gujarat riots a year earlier takes the form of an act that shows how a nation diminishes itself as it violates the promises of its founding fathers in a striking symbolic display of self-harm. At a time when the country’s Constitution is threatened by divisive forces, Kallat’s warning seems to acquire a perverse relevance.

Gandhiji’s words of restraint promoting non-violence as a living ideal are re-conceived by Kallat in two subsequent works – Public Notice 2 (2007) has bone-shaped fibreglass sculptures spelling out the text of his famous Dandi March speech and Covering Letter (2012) carries the text of his letter to Hitler beamed on a fog screen. Public Notice – 3 extends Kallat’s critical echolocation of heroic voices by installing the text of Swami Vivekananda’s iconic Parliament of Religions speech about “the religion which has taught the world both tolerance and universal acceptance” on the grand staircase of the Art Institute of Chicago. This was where it was delivered exactly 108 years before 9/11. Kallat renders the words with LED lights using the U. S. Homeland Security threat code display protocol. As bigotry re-incarnates in different avatars all around the world, the fate of people who refuse to learn from history acquires a new ironic ring.

Atul Dodiya. Antler Anthology X. Watercolour, charcoal and marble dust on paper. 84” x 60”. 2004. Image courtesy of the artist.

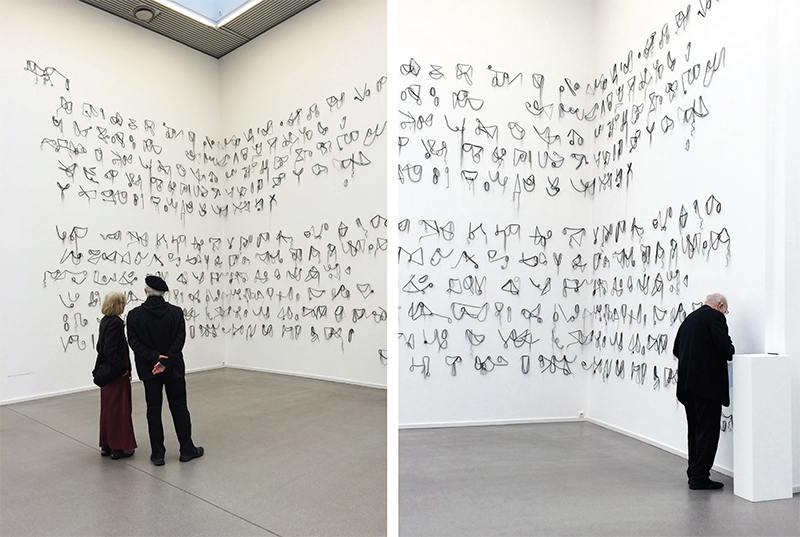

In many of her installations and performances, Mithu Sen has explored the anarchic possibilities of translating thought across languages. Experiencing linguistic anxiety after relocating from Bengali-dominant Santiniketan to English and Hindi-dominant Delhi, she began to probe normativities, especially those involved in disciplining gendered subjectivities, as part of an investigation into crises of belonging. no STAR, no LAND, no WORD, no COMMITMENT… (2004, 2010, 2014) was an attempt at creating a new alphabet out of artificial hair-clumps arranged against a wall in a variety of shapes – viewers were invited to interpret the indeterminate writing and relate it to their own experiences. Interestingly, from Jeram Patel’s blow-torched forms to Manisha Parekh’s mixed mediatic sculptural pieces, quite a few artists have developed shape-clusters that look like abstract scriptorial elements.

Sen has two books of published poetry in Bengali – Basmati Body Garden or Song (1995 – 2005) and I am a Poet (2013 – 14), and in her performances and videos, has experimented with expansive non-languages – forms of verbal communication that are partially recognizable, ill-defined or corrupted. In I have only one language; It is not mine (2013 – 14), for instance, Sen donned the garb of Mago, a homeless person, and lived for a few days in an orphanage in Kerala, speaking to everyone in gibberish. Pushing the boundaries of what constitutes communication, Sen dug deep into non-verbal, gestural and haptic modes of forging bonds. The tyrannical stranglehold of the grammatical utterance often hinders the flow of emotion, maintains Sen, and her Instagram project Un-poetry for the last four years, involves cryptic text that flashes on the screen sounding contrary – its deliberate naivete, attempted aphoristic sting and mix of silliness and sophistication helps generate a brief but sharp spell of contemplation. One of the posts recently read, “(mithusen26): This message is no longer available because it was unsent by the sender”.

Boston-based Youdhisthir Maharjan’s works involve an awareness of the spaces that words occupy and the contours they confirm. Plucking out letters precisely from pages, re-claiming their bodies, and re-appointing them in startling new positions, Maharjan envisages new roles and new destinies for the written word. He also incense-burns them, connects them in new cuneiforms, paints over them to create a layer of arabesques and constellatory patterns. Like Dodiya, Maharjan is moved by the book as an object that records life and its movements – for instance, he has pasted the pages of Nelson Mandela’s inspirational autobiography Long Walk to Freedom to create a continuous scroll, arguably a freer, less bounded form that opens up to the world and unshackles meaning. In Saubiya Chasmawala’s Batin (2019) at Tarq, Mumbai, Arabic letters are rendered on paper with a performative flourish to release charged formal patterns. The gesture of continuously repeating shapes – the curls, the curves, the swirls – is liberating but also paradoxically leads to the celebration of an overwhelming desire to shroud, shadow and envelop.

Mithu Sen. no STAR, no LAND, no WORD, no COMMITMENT…Site-specific installation. Size variable. 2004, 2010, 2014. Image courtesy of the artist.

In Reena Saini Kallat’s latest show at Chemould Prescott Road, Mumbai (2019), the eponymous installation Blind Spots (2017-19) involves Snellen eye screens featuring the slow scrolling of letters that compose words culled from preambles of constitutions of seven warring nations. As you listen to the audio, your head stuck in a toilet plunger-shaped equipment, the screens before you display words like ‘justice’ and ‘democracy’ dematerialising into faux-braille dots. These are life-affirming ideals that are shared by enemy nations.

This cruel insistence on blindness (to values, cultures, languages and aspirations common to people belonging to adversarial countries) and its deliberate cultivation has been examined earlier by Kallat in works like Verso-Recto-Verso-Recto (2017-19). This work comprised cloth scrolls with inscribed preambles of five pairs of opposing nations. In 2007, Kallat rendered her mother’s recipes on hanging sarees in braille. Walls of the Womb was an attempt at decrypting words by touching them as they came from far way, from the notebook of a dear one who was dead. As Kallat pursues hybridity as an enabling proposition in much of her current work, she also dwells on the experience of mutability in quite a few of her installations – Saline Notations (Echoes), 2015, comprises a series of texts written in salt on a beachfront which the tides slowly rush to claim. Comprising difficult questions probing the politics of mutuality the text leaves you meditating about the inevitability of erasure, the inescapability of loss.

Saubiya Chasmawala. Untitled #38. Ink on paper (HSN Code:9701). 8.4” x 11.7”.2019. Image courtesy of the artist and Tarq. © Saubiya Chasmawala.

From distributing bottles filled with a red liquid labelled Blame (2002-03) in the wake of riots in Gujarat to mounting an installational homage to 100 persecuted poets, Shilpa Gupta has always contested unjust power equations. In For, In Your Tongue, I Can Not Fit (2017-18), poems are seen speared on papers as you hear them being recited in a dimly lit room. Someone Else (2011) is a sculptural homage to writers who have been censored or have used assumed names. Gupta has often probed words for hidden depths – outdoor light or animated installations like ‘We change each other’ (2017) and ‘Deep below, the Sky flows under our Feet’ (2016-17), in different scripts, try to forge a new audience for public art. The etched marble slabs for anonymous graves (2013) and suitcases with ‘There is no explosive in this’ (2007) written on them are attempts at interactively confronting the culture of fear and foregrounding state repression.

Nalini Malani. Can you Hear Me? (Detail). iPad Animation. 2019. Image courtesy of the artist.

A roomful of iPad animations unleash colourful flashbursts and generate overwhelming sounds to beam mini-narratives about rape and disenfranchisement, corruptions of power and the institutionalisation of violence – Nalini Malani’s latest show Can You Hear Me? (2019) at Max Mueller Bhavan, Mumbai, is an immersive experience with disjointed episodes playing simultaneously on wall-screens. The animations both compete for attention and leak meaning into each other. Flickering prominently are lines from poems by Wislawa Szymborska and Faiz; observations by George Orwell, Hannah Arendt and Milan Kundera; and extracts from plays by Samuel Beckett and Bertolt Brecht. Malani’s critique of the devastation engendered by routinized hatred recalls Remembering Toba Tek Singh (1998), a videoplay about a vivisected people in a post-Partition landscape who are traumatised by real and symbolic monsters unleashed by the nuclear arms race. Inspired by Saadat Hassan Manto’s telling short story, Remembering Toba Tek Singh comes on the heels of The Job (1997), an experimental mix of video sculpture, animation and performance, based on the story by Bertolt Brecht. Firmly committed to interrogating market manipulations, Malani often mines literary and mythic material to critique the continuous pathology of subjugation and exploitation.